Volume XIII: Sermons Preached in St Paul's Cathedral, 1626-1627

Volume Editor: Mary Ann Lund

It is an irony that the word ‘declination’ recurs in Donne’s sermons preached at St Paul’s cathedral during 1626 and 1627, a period when he was at the height of his rhetorical powers. The word is one of Donne’s favoured terms for the human propensity to sin: ‘to bend downwards upon the earth, to fix our breast, our heart to the earth, to lick the dust of the earth with the Serpent [. . . ] this is a manifest Declination from this Uprightnesse’ (3rd Prebend, 5th November 1626). In his funeral sermon on Sir William Cokayne (12 December 1626), however, the word becomes an image of strength made perfect in weakness:

there is no forme of Building stronger then an Arch, and yet an Arch hath declinations, which even a flat-roofe hath not; The flat-roofe lies equall in all parts; the Arch declines downwards in all parts, and yet the Arch is a firme supporter. Our Devotions doe not the lesse beare us upright, in the sight of God, because they have some declinations towards natural affections.

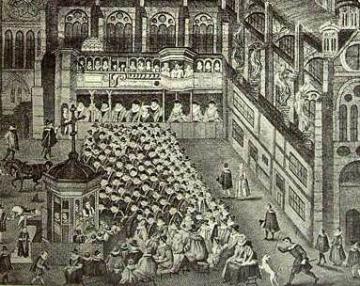

The architectural metaphor not only supports individual (and necessarily frail) acts of devotion, but contains those acts within a ‘Building’. Donne’s sermons in 1626-7 show a sustained interest in the relationship between private and public prayer, and treat the space of the St Paul’s cathedral choir – the location of the pulpit from which he preached – as the heart of true devotional practice: a powerful, spiritually charged location, the communion of saints in miniature. His Whitsunday 1627 sermon ends by reminding the auditory that great buildings have high turrets but deep foundations, and that, ‘As in this place, where you stand, their bodies lies in the earth, whose soules are in heaven; so from this place, you carry away so much of the true comfort of the Holy Ghost, as you have true sorrow, and sadnesse for your sins here’.

While the arch of the Cokayne sermon imagines individual worship as a physical structure, six weeks later another kind of curve locates ‘true religion’:

In the state of nature, we consider this light [the knowledge of God], as the Sunne, to be risen at the Moluccae, in the farthest East; In the state of the law, we consider it, as the Sunne come to Ormus, the first Quadrant; But in the Gospel, to be come to the Canaries, the fortunate Ilands, the first Meridian. Now, whatsoever is beyond this, is Westward, towards a Declination. (4th Prebend, 28th January 1626/7)

To go further than to be Christians, he continues, to ‘call our selves, or endanger, and give occasion to others, to call us from the Names of men, Papists, or Lutherans, or Calvinists’, is to depart from ‘the true glory and serenity, from the lustre and splendor of this Sunne’. Donne’s rejection of confessional labels reflects a careful positioning of ‘this Church’ between extremes during this period. The Christmas 1626 sermon includes a lengthy discussion of responses to the eucharist (‘the Roman Church hath catched a Trans, and others a Con, and a Sub, and an In’), while the Candlemas sermon revisits one of his earliest analogies (from his Paul’s Cross sermon, 24th March 1616) to the Catharists and Cathari, false ‘Puritans’ of different stripes; on this occasion, the Roman Church becomes ‘a third state of Puritanes’, ‘Super-cathari’ who believe that men may become pure enough on earth to achieve familiarity with God.

The militant anti-Catholic (and, more pointedly, anti-Spanish) tone of the earlier 1626 sermons (Volume XII) can still be heard in this volume, but, after the failure of the 1626 parliament to supply Charles I with the finance for continental war, Donne’s targets subtly shift. The early sermons in this volume still register the aftermath of that session, as in Donne’s allusion to being ‘a Subsidy man’ to pay God’s debts (3rd Prebend), or his veiled warning in the Ps. 32: 7 sermon that ‘If there be no way but Force and Armes’ to oppose the Roman Church, ‘God bee blessed that keepes us from the necessity, but God bee blessed also that he preserves us from perplexity, or not being able to defend his cause, if he call us to that triall’. As the legal year goes on, however, his attention turns to conflicts within the English church, and to the importance of outward expressions of conformity: church attendance, kneeling, taking communion.

This change is in part motivated by a shift in the composition of Donne’s auditory. Whereas many of the 1626 sermons in Vol. 12 are addressed partly towards Members of Parliament and Convocation, the sermons in this volume are not preached during a parliamentary session, and are more explicitly aimed at London citizenry: the city corporation, merchants, commercial tradesmen. This is most obvious in the Cokayne funeral sermon, a text whose rhetoric and context have been richly elucidated by Peter McCullough. This volume benefits from the detailed analysis and archival evidence uncovered by McCullough, and extends it by showing how that occasional sermon forms part of a tightly cohesive group preached between November 1626 and February 1627. In its most well known passage,

I throw my selfe downe in my Chamber, and I call in, and invite God, and his Angels thither, and when they are there, I neglect God and his Angels, for the noise of a Flie, for the ratling of a Coach, for the whining of a doore.

Although this moment of seeming confession is a strikingly distinctive one, the theme is revisited throughout that winter at St Paul’s. His Christmas sermon emphasises that God works differently in ‘places consecrated to his service, then in every prophane place. When I pray in my chamber, I build a Temple there, that houre; And, that minute, when I cast out a prayer, in the street, I build a Temple there’, but ‘shall I not come to his Temple, where he is alwaies resident?’. Similar comparisons between the function and effectiveness of prayers in a street, a chamber, and the congregation are made in the Fourth Prebend sermon and the Candlemas sermon. Donne clearly expects that the same auditory will hear him preach on multiple occasions, and indeed remarks on auditory’ responses to repetition in the Candlemas sermon: ‘Did not I heare this Point thus handled in your Sermon, last yeare? Yes, must he say, and so you must next yeare againe, till it appeare in your amendment, that you did heare it’. The revisiting of ideas is, for Donne, a pastorally motivated strategy.

One further parallel illustrates the change in Donne’s preaching during 1626. In his Psalm 32: 6 sermon (OESJD Vol. 12, Sermon 4), dated by this edition to the spring of that year, he uses the topography of London and its environs to attack Catholic practice in prayer (a topic controversially handled by Richard Montagu in 1624): ‘Certainely it were a strange distemper, a strange singularity, a strange circularity, in a man that dwelt at Windsor, to fetch all his water at London Bridge: So is it in him, that lives in Gods presence, (as he does, that lives religiously in his Church) to goe for all his necessities, by Invocation to Saints’. Even worse, he suggests a little later, those who go to London Bridge, ‘they will go lower, and lower, to Gravesend too; They that come to Saints, they will come to the Images, and Reliques of Saints too’. In his funeral sermon on Cokayne, preached in December, he recasts the idea in terms of commerce and the law as an argument for worship within the church: ‘He that hath a cause to be heard, will not goe to Smithfield, nor he that hath cattaile to buy or sell, to Westminster; He that hath bargaines to make, or newes to tell, should not come to doe that at Church; nor he that hath prayers to make, walke in the fields for his devotions’. Donne’s target is now sectarianism, while his analogy moves from the royal court to the market place, the world of the wealthy London citizen.

While declinations in faith, devotion, and religious identity are at the forefront of Donne’s mind during 1626-7, thoughts on physical decline also mark his St Paul’s sermons of this period. At Christmas in 1626, he expands on the body-as-prison theme to dwell on the ravages of illness and ageing:

Our prisons are fallen, our bodies are dead to many former uses; Our palate dead in a tastlesnesse; Our stomach dead in an indigestiblenesse; our feete dead in a lamenesse, and our invention in a dulnesse, and our memory in a forgetfulnesse; and yet, as a man that should love the ground, where his prison stood, we love this clay, that was a body in the dayes of our youth.

At Easter, Donne reworks this meditation in the first-person singular as he looks forward to the ‘Better Resurrection’, ‘when I consider what I am now, (a Volume of diseases bound up together, a dry cynder, if I look for naturall, for radicall moisture, and yet a Spunge, a bottle of overflowing Rheumes, if I consider accidentall; an aged chide, a gray-headed Infant, and but the ghost of mine own youth)’. Donne’s use of himself as an embodiment of his sermon’s ideas (a tactic he most famously employs in Deaths Duell) mirrors his use of William Cokayne’s body as ‘this Text which you See’ in his funeral sermon. His Easter sermon is deeply personal, preached partly at least to a congregation of fellow-clerics who knew him well, and knew of the death of his daughter Lucy in January. Donne uses Thomas Aquinas’ Super Epistolam B. Pauli ad Hebraeos Lectura to reject earlier expositors’ interpretation of his text (Hebrews 11: 35: ‘Women received their dead raised to life againe’) as being about wives and dead husbands; instead, like Aquinas, he affirms that the women are ‘Mothers that had their Children raised to life’. Donne’s exegesis allows him to use his own example in a moving reflection on grief: ‘This is the faith that sustaines me, when I lose by the death of others, or when I suffer by living in misery my selfe, That the dead, and we, are now all in one Church, and at the resurrection, shall be all in one Quire’. Comfort is imagined through the space of the preaching venue, which becomes the representation not only of the church militant on earth, but also of the church triumphant in heaven.

SERMONS CONTAINED IN THIS VOLUME

- Preached upon the Penitentiall Psalmes. [Ps. 32: 7]

- Preached upon the Penitentiall Psalmes. [Ps. 32: 8]

- Preached upon the Penitentiall Psalmes. [Ps. 32: 9]

- Preached upon the Penitentiall Psalmes. [Ps. 32: 10, 11]

- The Third of my Prebend Sermons upon my five Psalmes: Preached at S. Pauls, November 5. 1626. In Vesperis.

- Preached at the funerals of Sir William Cokayne Knight, Alderman of London, December 12. 1626.

- Preached at S. Pauls upon Christmas day. 1626.

- The Fourth of my Prebend Sermons upon my five Psalmes: Preached at S. Pauls, 28. Ianuary, 1626 [1626/7]

- Preached upon Candlemas day. [Matt. 5: 8. 1626/7?]

- Preached at S. Pauls, upon Easter-day. 1627.

- Preached at S. Pauls, upon Whitsunday. 1627.

- The fifth of my Prebend Sermons upon my five Psalmes: Preached at S. Pauls. [1627]

- Preached at Pauls, upon Christmas Day. 1627.